In June of 1949, Ben Chifley delivered his famed “Light on the Hill” speech to the NSW ALP Conference. Chifley outlined Labor’s meaning and purpose, as he understood it:

“I try to think of the Labor movement, not as putting an extra sixpence into somebody’s pocket, or making somebody Prime Minister or Premier, but as a movement bringing something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people. We have a great objective – the light on the hill – which we aim to reach by working the betterment of mankind not only here but anywhere we may give a helping hand. If it were not for that, the Labor movement would not be worth fighting for.”

Of all the remarkable acts of oratory through the ALP’s history, none has been so successful in articulating the party’s guiding principles and purpose. It was a speech that only Ben Chifley could have delivered.

Chifley was a defining influence on Labor’s history – and his is a story that should be better known. It is a story that that contains important lessons for the ALP as it undertakes the immense challenge of implementing its ambitions for change through the political system.

Who was Ben Chifley?

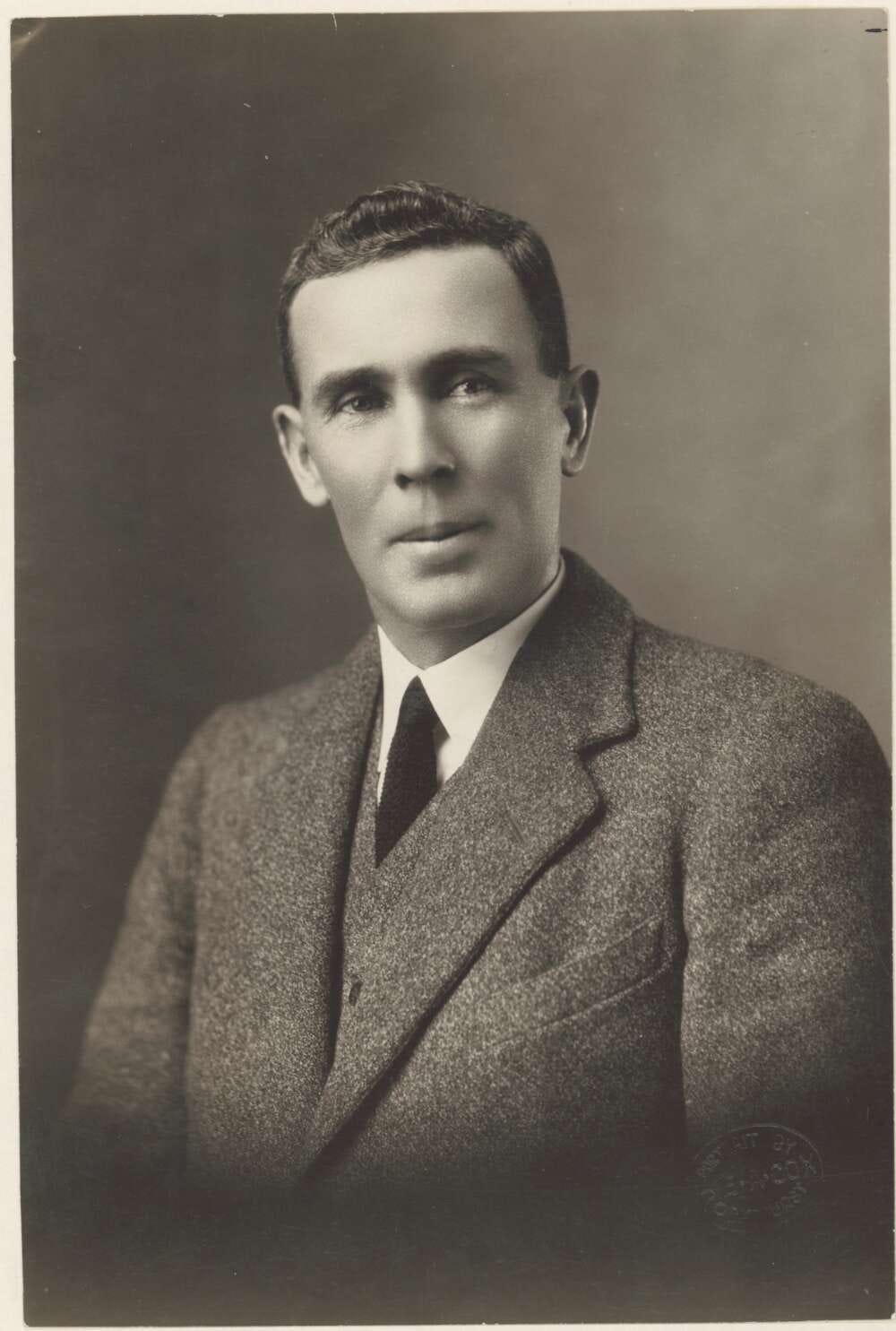

Ben Chifley was born in Bathurst in NSW in 1885. Throughout his life he would remain immensely proud of his Bathurst roots.

Aged just five years old, he left his home to live with his grandfather at his small farm outside of town. His childhood was inflected with the deep misery caused by the economic depression of the 1890s – a global malady that struck Australia particularly hard.

Chifley had limited educational opportunities at the time, but was voracious in his self-education. He had an indefatigable drive to self-improvement and a thirst for knowledge that allowed him to overcome the limitations of his schooling.

As a young man he joined the NSW Railways, working through the day and studying four nights a week at the Workers’ Educational Association. He went on to qualify as a first-class engine driver (at his qualification he was the youngest in the state).

He was dedicated to his profession, later saying that the train’s whistle and engines were like ‘music to me’. He was also a committed trade unionist.

In 1917 a mass strike broke out across NSW. Chifley was prominent in leading the union’s activities in the Bathurst area, exposing him to victimisation when the strike was finally broken. At first he was sacked outright, but was later reinstated to a more junior position, being forced to report to men he had previously trained.

Chifley’s parliamentary career began in 1928 when he was elected as the Member for Macquarie. The following year, James Scullin led Labor back to federal government for the first time since 1916. And then came the crash.

Scullin’s Government was swamped by the international cataclysm of the Great Depression. These were deeply polarising times, and NSW Labor eventually split with Jack Lang’s supporters helping bring Scullin down. Chifley, serving as Minister for Defence, lost his seat in the anti-Labor swing at the 1931 election.

In the years that followed Chifley, now out of office, played a central role in holding Labor forces in the state together against the onslaught of Lang and his myrmidons. Chifley even took Lang on in his own seat of Auburn at the 1935 state election, unsuccessfully.

That same year Chifley was appointed to the Lyon Government’s Royal Commission into banking and finance. He threw himself into his responsibilities with diligence and determination. Though he lacked formal qualifications in the study of economics and finance, his extraordinary capacity for self-education ensured that he held his own in its deliberations. He engaged deeply with the new ideas of international economics, such as those propounded by John Maynard Keynes.

Chifley re-contested and won Macquarie at the 1940 election. He was plagued by pneumonia through the campaign and relied on friends and comrades to act as his proxies. It was close – he only squeaked through on preferences – but it was enough. Chifley was back in Canberra, in another moment of extraordinary national crisis as the Second World War raged.

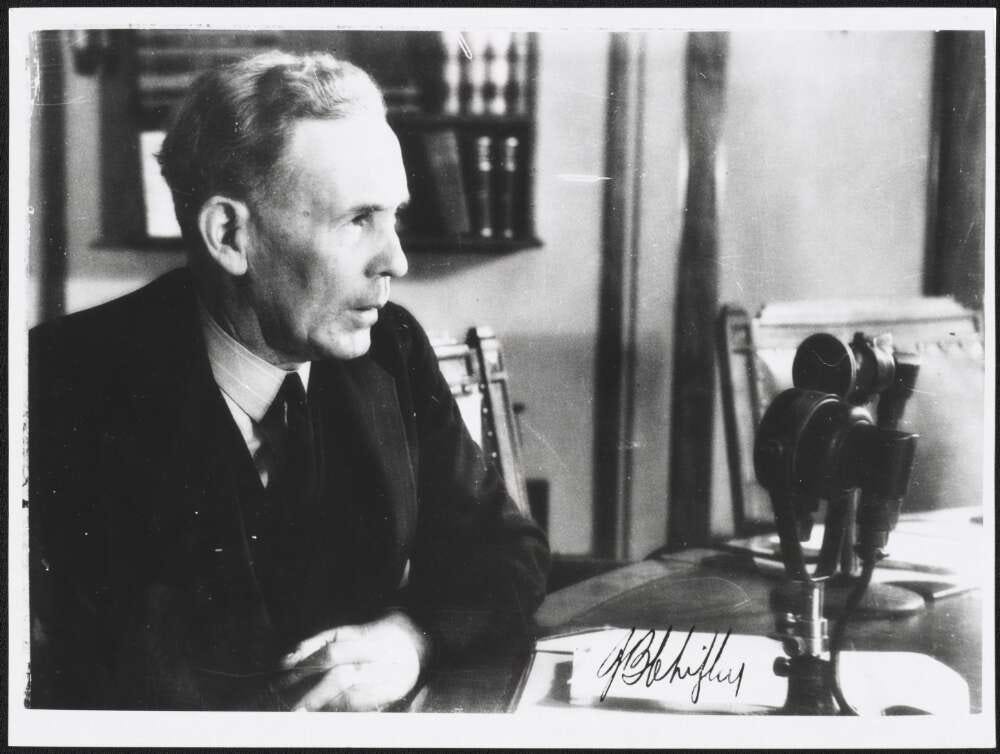

In October 1941, John Curtin became prime minister after two independents decided to back a minority Labor Government. Chifley was appointed as Curtin’s Treasurer. Their relationship would become one of the most significant political double-acts in Australian history.

Curtin relied greatly on Chifley and trusted his capacities to undertake the extraordinarily difficult task of managing the nation’s finances in a time of war. Chifley had to fund the war effort without falling into the debt trap that had befallen Australia during the First World War.

In 1942, Curtin entrusted Chifley with the Ministry of Post-War Reconstruction. This Ministry was the centre of the government’s plans to transform Australia into a fairer and more egalitarian country after the war was won. Combined with his continued position as Treasurer, it was an extraordinary workload that few others would have been able to sustain.

In the final stages of the war, Curtin was suffering from failing health exacerbated by the strains of wartime leadership. It was increasingly Chifley who stepped into the breach. After Curtin died in office in July 1945 Chifley was persuaded by caucus colleagues to stand for the leadership. Chifley was elected by an overwhelming majority.

Prime Minister Chifley

After his ascension to the Prime Ministership, Chifley maintained a herculean workload. Determined to see through Australia’s economic transition from the war economy to post-war reconstruction, he maintained the Treasury portfolio even while serving as PM.

Not even Curtin had attempted that, a senior public servant remarked.

‘Yes, but he had me,’ came Chifley’s reply.

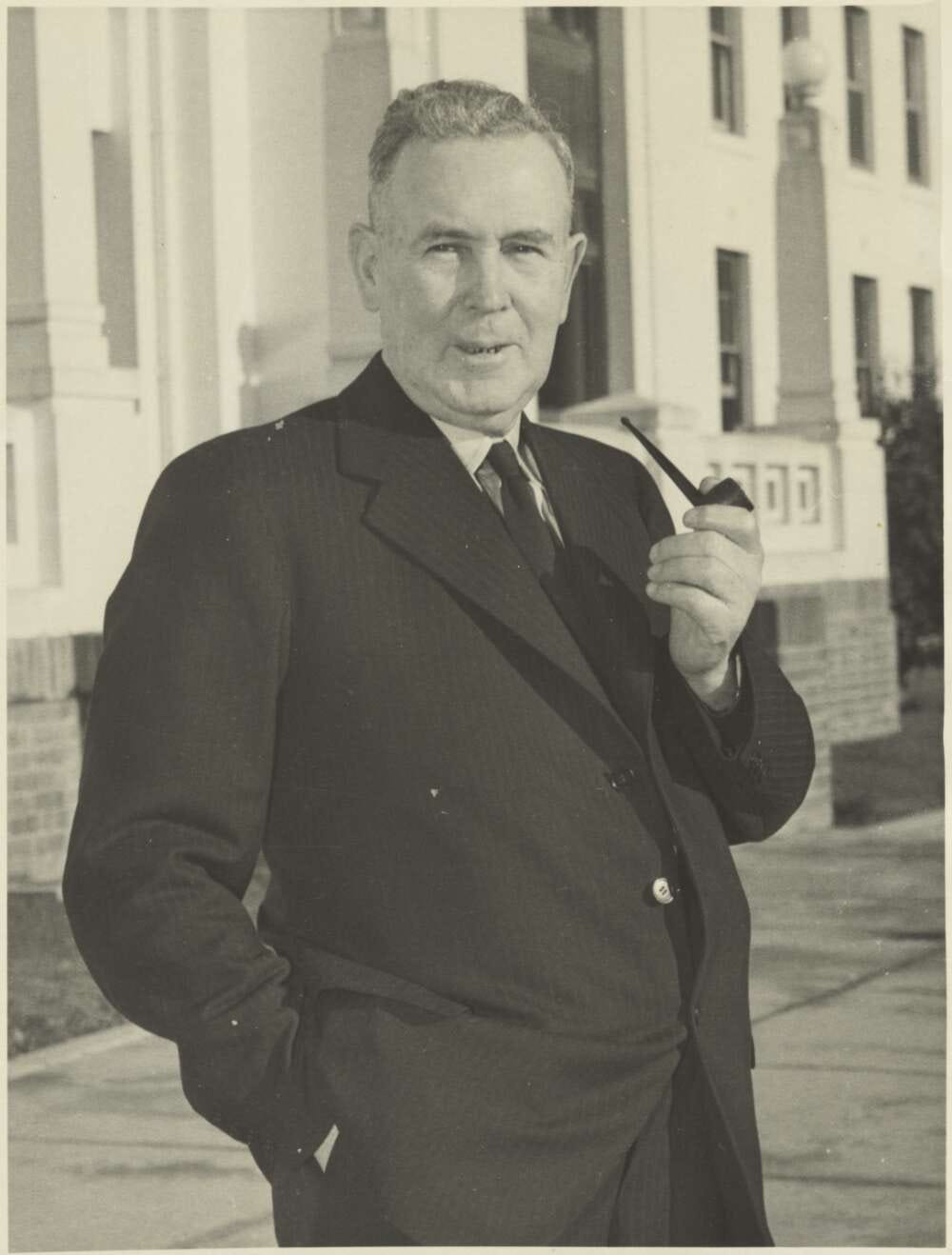

The powers and extraordinary responsibilities of the office did not change Chifley. He was still known for his kind-heartedness, modesty, and generosity. He eschewed the formality of The Lodge for a small room at the Kurrajong Hotel where he felt more comfortable.

He was indefatigable in his pursuit of Labor’s program.

It has often been noted that Chifley was a leader of great practicality. But equally, he was driven by principle. He understood the need to balance these two elements of a successful Labor government, and not to be driven to either extreme.

The government was guided by its policy of full employment. This would ensure Australia would not return to the devastation of mass unemployment seen during the Great Depression. But the policy of full employment was also a recognition that the Australian people had the right to expect employment and that the government had the responsibility to take the positive action that would provide it.

The Chifley Government undertook an extensive reform effort to ensure that returned soldiers were not just resettled. bit had access to the vital supports and opportunities that would allow them to flourish after the war had been won.

Government investment helped spur new industries and ongoing economic expansion.

Under Chifley’s leadership the program of post-war migration began, the Snowy Mountain Scheme was inaugurated, the Australian National University established, and the first Holden produced entirely in Australia rolled off the production lines. Between 1941 and 1949 pension levels doubled.

Chifley’s government set the basis of the post-war economy that would see economic growth based on full employment for decades to come. It was an extraordinary achievement that expanded opportunities and made Australia a far more equal place than it had been before the war.

This came with its limitations. For instance, Chifley’s government maintained support for the racist White Australia policy. It was still a period of other racialized and gendered exclusions and should not be idealised. These attitudes should neither be ignored nor excused. They need to be recognised so we can learn and do better today.

While the Chifley government put in place the foundations for the growth to come, the immediate post-war years were still beset by restriction. Rationing remained in place. There were severe supply shortages.

Such privations were widely understood as a product of the war years, and Chifley was returned at the 1946 election. But at the same poll, two out of three proposed referendums which would have provided greater control necessary to manage the transition from a war to a peacetime economy were rejected. Frustrations grew among Australians as years passed and the restrictions on consumption remained in place.

Difficulties compounded. In 1947 the High Court ruled part of the 1945 Banking Act to be unconstitutional. Chifley announced a plan to nationalise the banks.

The banks mobilisied in opposition. They drew on seemingly unlimited funds to denounce Chifley’s plans as socialistic. Bank employees were encouraged to canvass. Fears of economic devastation were spread widely. The government’s credibility was damaged.

Ultimately, the High Court ruled the bank nationalisation legislation to be unconstitutional anyway. Chifley endured two years of sustained reputational damage by this orchestrated campaign against his government.

The immediate post-war consensus was falling apart. Unions refused to endure further delay for long-promised wages and conditions. Chifley was determined to prevent an mass outbreak of inflation similar to that which had occurred following World War One, and insisted on wage discipline. Communist unions became increasingly antagonistic. In 1949 a long and bitter coal strike broke out.

The coal strike was an immense strategic mistake by communists in the union’s leadership who believed the time was ripe for aggressive action. But Chifley’s response engendered great bitterness. Fearing total economic breakdown Chifley authorised special legislation that led to the arrest of union leaders. The army was mobilised to work in the mines. The strike collapsed.

Soon after, Chifley called the election.

These were the waning days of Labor’s golden age. Chifley repeated the imagery of the Light on the Hill in his election policy-speech later in the year. Chifley was exhausted. After eight years of extreme exertions in Australia’s service, his health was failing. The 1949 election was a seismic victory for Robert Menzies and the conservative coalition.

He remained as party leader after the poll. The political tensions that would metastasise into the DLP spit were emerging. In June of 1951, Ben Chifley, still Labor leader, died of a heart attack.

The Light on the Hill is still burning

As Treasurer and then Prime Minister, Ben Chifley played a defining role in a time of immense national crisis and transformation. His significant contribution to Australian history should be better recognised today.

But his significance is not just historic.

Chifley modelled a distinctively Labor form of leadership. It was one that addressed the immediate problems Australia faced, but did so in a way that built for long-term success. It was a form of leadership that acknowledged the need to be practical and pragmatic in pursuit of Labor’s aims – but understood that this pragmatism had to be underpinned by a strong commitment to distinctively Labor principles.

This is what gives the Light on the Hill speech, and the story of the man who delivered it, its power. The speech was so significant because it was a touchpoint, a moment of transmission and inheritance. The specific policies Labor would pursue in the time to come would of necessity change to reflect modern Australia. But Labor’s mission of “bringing something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people” endured. It is this mission that has given Labor a unique place in the political firmament. It is an ongoing touchstone, a means to preserve and protect our meaning and identity as a party.

As long as there is a Labor Party we will be striving to reach that light on the hill. And though Chifley’s time has come and been, that light is shining still.

This article is also published on Liam Byrne’s Substack blog, Maintain Your Rage – CLICK HERE